Saturday, May 31, 2008

Bonobo Fission-Fusion

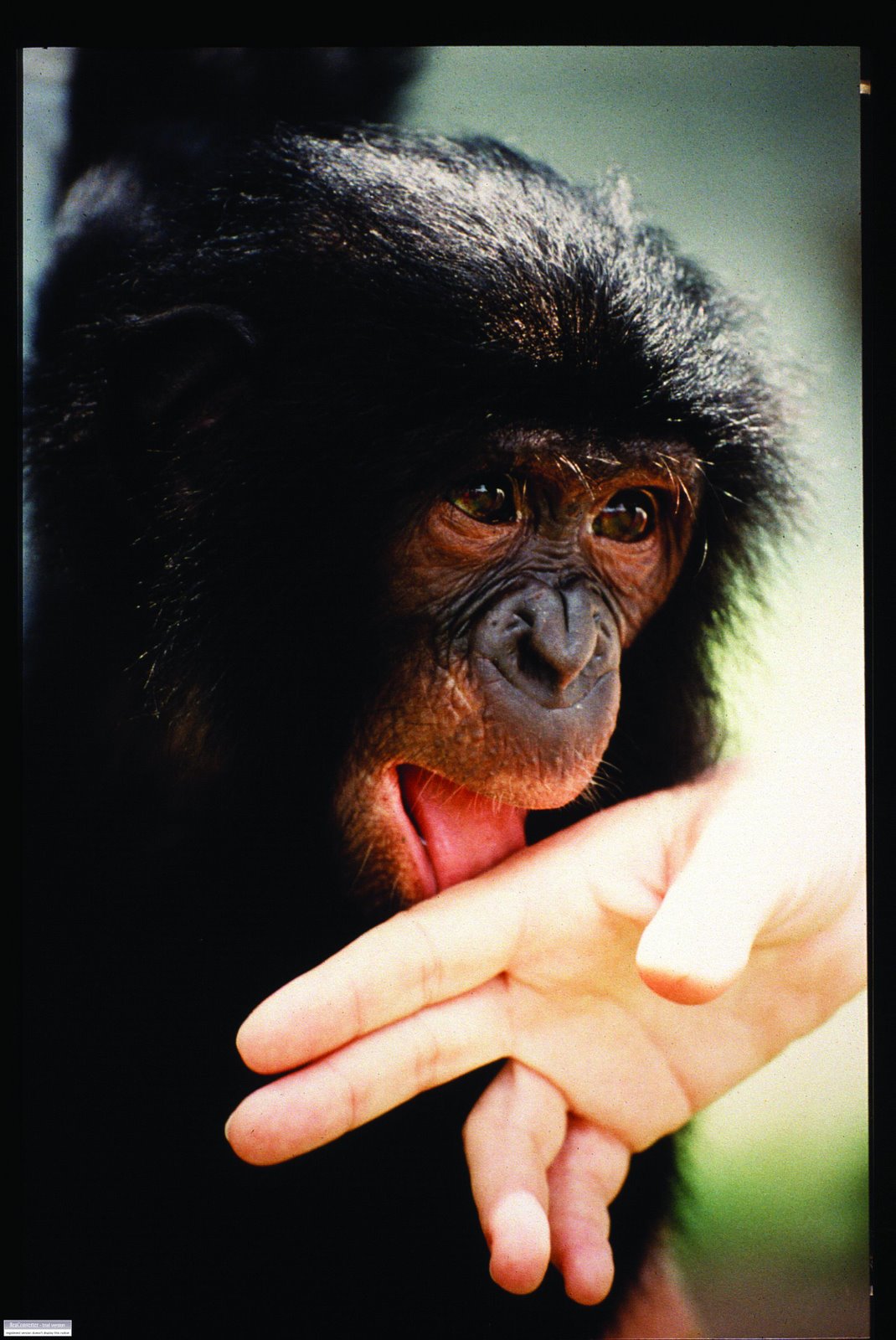

These bonobos live at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens. They are managed in a mix-and-match fashion that mimics the wild. From Grains of Golden Sand, "Bonobos live in a “fission-fusion” society; group size constantly fluctuates. Groups and individuals meet like wayward atoms and molecules, mingle, then remix and disperse based on the dynamics of the moment. A female with her offspring might form a small band that forages apart during the day but nests for security at night with the extended group. Groups may meet in assemblies of 50 or more to share fruiting vegetation. On the other hand, they may party for purely social reasons, such as banging on the drum-sounding buttress roots of canopy trees and having a bonobo fiesta of a good time."

Fission-fusion in captivity is where zookeepers put differing animals together based on subtle, social cues as to compatibility and the animals' desires to mingle. They then swap out individuals to permit proper and ongoing socialization. In all cases the keepers cannot force the animals to move against their will -- they only extend "invitations" (with enticements of food treats and toys) to come or go, or to mix or not. At times the animals themselves choose their movements (outdoors, on exhibit, or indoors in the night-house) as well as their companions. Fission-fusion follows the natural model for the species and is a simple way to spice up and enrich bonobo lives.

Friday, May 30, 2008

Dr. Jo Thompson and Mvula

Dr. Jo Thompson, Director of the Lukuru Wildlife Research Project, is a renowned wildlife biologist who has lived and worked in the most remote regions of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for the past 17 years. She has primarily worked on studying and protecting the bonobo, as well as being a leader in partnering with the local people.

Continuing to work throughout most of a 10 year war in the DRC, Jo organized a pioneering effort to support conservation work in the DRC protected areas throughout the worst years of the war. She led a one-of-its-kind mission of top Congolese conservationists to meet with Security Council member state ambassadors at the United Nations while continuing field activities under the most challenging conditions. These contributions distinguished her as an internationally acclaimed real-world conservationist, for which she was awarded the title of 2004 Rolex Awards for Enterprise Associate Laureate.

Jo received her doctorate degree from the University of Oxford, England; Master's degree from the University of Colorado, Denver; and her Bachelor's degree from Wittenberg University, Ohio. She is a member of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group and most recently co-edited and contributed to a seminal book on bonobo conservation. Jo is a contributing author to several books regarding aspects of wild bonobo ecology, distribution and evolution. She has published multiple articles in peer-reviewed and popular wildlife and conservation journals and magazines.

Jo's research site is in the southernmost region of the bonobo's range, where dry, patchy forest is found in galleries along the watercourses and savanna on the hilltops. The story of how she first met a wild bonobo can be read in Grains of Golden Sand (Bonoboas and Driver Ants).

What distinguishes Jo is her appreciation and understanding of the local people. This grassroots approach led her to purchase, within the tribal system, a vast tract of terrain for her bonobo research.

Featured in this photo is Mvula, Dr. Thompson's field assistant. She says about him, "Mvula has worked with me for 15 years. He is one of the -- if not THE -- best bonobo trackers in the country ... a skill he learned over the years as we worked together. He is also the project leader in the management of the Bososandja Domaine Naturelle. He is very well known throughout the Lukuru region and highly respected. He has a wonderful sense of humor and is very loyal to bonobo conservation. He is a great guy. I trust him with my life."

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Peace Corps Writers Review

I left for Zaire in 1984 to serve in the Peace Corps. The following is excerpts from a review posted on the Peace Corps Writers Site: http://www.peacecorpswriters.org/

Reviewed by Jan Worth-Nelson (Tonga 1976–78)

"IN THE FIRST SCENE of Delfi Messinger’s big and ambitious memoir, it is September 24th, 1991. In the streets of Kinshasa, Zaire, machine guns ack-ack on the streets as soldiers mutinying against the corrupt Mobutu Sese Seko, Zaire’s “president for life,” rampage from door to store, hundreds of others joining them in a frenzy of looting, vandalism and murder. Messinger, stranded within the compound of the National Institute of Biomedical Research where she both works and lives, is terrified.

With the Institute and its multi-million-dollar stock of equipment and supplies “abandoned to fate,” she makes a desperate decision. Still in her white lab coat, she grabs a pistol and rushes to the Institute’s sheep pasture. There she singles out and chases down one animal. She ropes its legs, and she shoots it. Then she uses the animal’s blood to paint the word “SIDA” (AIDS) on the compound’s wall. It’s the only way she knows to keep the plundering hordes away, and it works. The bloody warning soaks into the concrete and stays for months thereafter, until embarrassed bureaucrats finally decree it whitewashed.

What we learn about Messinger’s fierce and intrepid character in this opening is just the beginning of a story which ultimately settles down to describe how she took on the mission of saving the Institute’s eleven bonobos, a rare and endangered species. Ultimately, after literally years of encountering bureaucratic resistance, getting caught up in life-threatening politics of conservation, and even once being kidnapped and interrogated for hours, Messinger succeeds — sort of....

As Messinger tries to save the bonobos, she lays bare her own vulnerabilities, confronting her fears and doubts with humor and self-deprecation. “What had I learned in the last ten years?” she writes in the book’s conclusion. “What had I accomplished for bonobos? Not a whole hallelujah lot . . . Zaire, Zaire, I’d loved you so! And oh, how I’d hated you. You taught me a lifetime of lessons . . . you gave me the human side of myself.”

But she did save six of the bonobos. There’s something poignant about the survival of this little band of peacemakers, and when Messinger finally flies out of the country with what must be one of the sweetest tribes of creatures on earth, the reader is hugely relieved. Yet one also worries on their behalf, hoping that humans and bonobos alike will stay around long enough to learn to keep their world intact."

Jan Worth-Nelson recently published a Peace Corps novel, Night Blind. Her poems, essays, short fiction and reviews have been widely published, and she teaches writing at the University of Michigan – Flint. She and her RPCV husband, Ted Nelson, commute between Michigan and Los Angeles.

Reviewed by Jan Worth-Nelson (Tonga 1976–78)

"IN THE FIRST SCENE of Delfi Messinger’s big and ambitious memoir, it is September 24th, 1991. In the streets of Kinshasa, Zaire, machine guns ack-ack on the streets as soldiers mutinying against the corrupt Mobutu Sese Seko, Zaire’s “president for life,” rampage from door to store, hundreds of others joining them in a frenzy of looting, vandalism and murder. Messinger, stranded within the compound of the National Institute of Biomedical Research where she both works and lives, is terrified.

With the Institute and its multi-million-dollar stock of equipment and supplies “abandoned to fate,” she makes a desperate decision. Still in her white lab coat, she grabs a pistol and rushes to the Institute’s sheep pasture. There she singles out and chases down one animal. She ropes its legs, and she shoots it. Then she uses the animal’s blood to paint the word “SIDA” (AIDS) on the compound’s wall. It’s the only way she knows to keep the plundering hordes away, and it works. The bloody warning soaks into the concrete and stays for months thereafter, until embarrassed bureaucrats finally decree it whitewashed.

What we learn about Messinger’s fierce and intrepid character in this opening is just the beginning of a story which ultimately settles down to describe how she took on the mission of saving the Institute’s eleven bonobos, a rare and endangered species. Ultimately, after literally years of encountering bureaucratic resistance, getting caught up in life-threatening politics of conservation, and even once being kidnapped and interrogated for hours, Messinger succeeds — sort of....

As Messinger tries to save the bonobos, she lays bare her own vulnerabilities, confronting her fears and doubts with humor and self-deprecation. “What had I learned in the last ten years?” she writes in the book’s conclusion. “What had I accomplished for bonobos? Not a whole hallelujah lot . . . Zaire, Zaire, I’d loved you so! And oh, how I’d hated you. You taught me a lifetime of lessons . . . you gave me the human side of myself.”

But she did save six of the bonobos. There’s something poignant about the survival of this little band of peacemakers, and when Messinger finally flies out of the country with what must be one of the sweetest tribes of creatures on earth, the reader is hugely relieved. Yet one also worries on their behalf, hoping that humans and bonobos alike will stay around long enough to learn to keep their world intact."

Jan Worth-Nelson recently published a Peace Corps novel, Night Blind. Her poems, essays, short fiction and reviews have been widely published, and she teaches writing at the University of Michigan – Flint. She and her RPCV husband, Ted Nelson, commute between Michigan and Los Angeles.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Showing Off A "Boo-Boo"

Kaleb and Lucy are half brother and sister bonobos at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens. Lucy appears to be checking something out on her thigh; a gesture that has caught the attention of Kaleb. The male has hair loss from over-grooming by the other animals because he is so popular in the group.

From the book, Grains of Golden Sand, "grooming is to clean either oneself—or, more likely another individual—of dried sweat, dirt, skin flakes, loose hair, scabs, lice, nits, and ticks. Not only does grooming clean the body of filth and parasites, but it reaches those hard-to-get-at places and is probably the most relaxing primate activity that exists. It is a generous massage offered by a subservient animal to a dominant one and serves to cement bonds of friendship. Primates groom a lot, and in captivity this behavior may become compulsive, which is one explanation for bald patches on over-groomed zoo apes."

Zoo apes do not have external parasites, but grooming is deeply ingrained. Zoo keepers provide stimulating environments to minimize over-grooming.

Photo by: M. Brickner

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Lucy Playing in Water

Lucy, a young female bonobo at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens is playing in the shallow moat in the exhibit. Her group is known to soak their hard "monkey biscuits" to soften them, as well as play with the fish and turtles that live in the moat. Bonobos are known to frequent pools in the wild and unlike other apes, they do not seem to fear water.

Photo by: M. Brickner

Monday, May 26, 2008

Grains of Golden Sand: Cows and Chickens

In the Peace Corps, learning a foreign language at the age of thirty was incredibly difficult, but what was more difficult was having to teach high school vet students in my labored French. From Grains of Golden Sand:

"No matter how I tried, I could not make myself understood. I struggled with lesson planning each night, spelling out by candlelight the next day’s lessons in phonetic longhand. I cheated by using the blackboard to outline the lesson with pictograms of stick cows and chickens and fences and connecting arrows. It was of little use; I was the laughing-stock of the entire school. I was nearing despair. At the rate I was progressing, my French would become decipherable just as I was finishing my Peace Corps tour.

Three weeks into the first semester, two things happened to change all that. I was struggling, red-faced, at the blackboard. It had been a morning of frustration. The torrent of rain clanging on the metal roof was so loud it was impossible to hold class. I was stuck in the dimness of the mud-walled room and chill of the tropical downpour, while the kids went wild in their boredom—there was not a scrap of reading material among them. They were not picking on me personally; that was just the way it was, but I was exasperated beyond expression. The downpour soon ended, but the distraction had thrown me. At that moment, I hated the school, my job, and the kids.

Laughter. Then twittering and chirping. From my position, I could see a gaggle of elementary-school boys in their blue and white uniforms hanging around outside the windows. They were giggling and pointing and egging on my students in Otetella, the local dialect. Discipline, in a school system known for its rigid and rough punishment of even minor infractions (for instance, Otetella was strictly forbidden in school) had reached a seemingly incurable low in my classroom.

Against the wall, just in front of where I stood, was a mound of crushed rock. It had been stored in the room—for some construction project, I supposed—for as long as I’d been teaching there. (Later, I was told that the classroom, locked at night, prevented theft of the valuable commodity.) I strode over, scooped up a double-handful of gravel, sneaked back, and hurled it out the window at the loiterers; stinging their legs and making them run for cover. I yelled, shaking my fist, “You! Get back in your classrooms where you belong!”

My own students broke into guffaws. I laughed with them to see the children, many of whom were little brothers, run off chastised.

“And you, too, listen up now!” to my students. Immediately, my classroom quieted. The young men gravely lifted their eyes to see what was coming next.

In slow, tortured French, I said, “I-am-your-teacher. All-of-you, not-me, must-take-the-state-exams.” I strung together the words, “If-you-want-to-pass, you-will-excuse-my-bad-French.”

That was the beginning of a new understanding. I continued to struggle with the language barrier and to draw pictures on the blackboard, but at least I had begun to win their respect."

"No matter how I tried, I could not make myself understood. I struggled with lesson planning each night, spelling out by candlelight the next day’s lessons in phonetic longhand. I cheated by using the blackboard to outline the lesson with pictograms of stick cows and chickens and fences and connecting arrows. It was of little use; I was the laughing-stock of the entire school. I was nearing despair. At the rate I was progressing, my French would become decipherable just as I was finishing my Peace Corps tour.

Three weeks into the first semester, two things happened to change all that. I was struggling, red-faced, at the blackboard. It had been a morning of frustration. The torrent of rain clanging on the metal roof was so loud it was impossible to hold class. I was stuck in the dimness of the mud-walled room and chill of the tropical downpour, while the kids went wild in their boredom—there was not a scrap of reading material among them. They were not picking on me personally; that was just the way it was, but I was exasperated beyond expression. The downpour soon ended, but the distraction had thrown me. At that moment, I hated the school, my job, and the kids.

Laughter. Then twittering and chirping. From my position, I could see a gaggle of elementary-school boys in their blue and white uniforms hanging around outside the windows. They were giggling and pointing and egging on my students in Otetella, the local dialect. Discipline, in a school system known for its rigid and rough punishment of even minor infractions (for instance, Otetella was strictly forbidden in school) had reached a seemingly incurable low in my classroom.

Against the wall, just in front of where I stood, was a mound of crushed rock. It had been stored in the room—for some construction project, I supposed—for as long as I’d been teaching there. (Later, I was told that the classroom, locked at night, prevented theft of the valuable commodity.) I strode over, scooped up a double-handful of gravel, sneaked back, and hurled it out the window at the loiterers; stinging their legs and making them run for cover. I yelled, shaking my fist, “You! Get back in your classrooms where you belong!”

My own students broke into guffaws. I laughed with them to see the children, many of whom were little brothers, run off chastised.

“And you, too, listen up now!” to my students. Immediately, my classroom quieted. The young men gravely lifted their eyes to see what was coming next.

In slow, tortured French, I said, “I-am-your-teacher. All-of-you, not-me, must-take-the-state-exams.” I strung together the words, “If-you-want-to-pass, you-will-excuse-my-bad-French.”

That was the beginning of a new understanding. I continued to struggle with the language barrier and to draw pictures on the blackboard, but at least I had begun to win their respect."

Sunday, May 25, 2008

Bonobos Playing "Store"

Lucy and Kaleb, two young bonobos at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, are engrossed with a cache of enrichment -- cardboard boxes, a shirt, plastic bucket, pine cones, palm fronds, and a rubber ducky -- provided by the keepers. They will spend hours playing, wearing, carrying, and destroying the items.

Lucy and Kaleb, two young bonobos at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, are engrossed with a cache of enrichment -- cardboard boxes, a shirt, plastic bucket, pine cones, palm fronds, and a rubber ducky -- provided by the keepers. They will spend hours playing, wearing, carrying, and destroying the items."Enrichment" is the term used by captive managers for those activities and objects that encourage natural behavior. The highly intelligent bonobo requires a socially healthy, stimulating, and complex enviromnent that the animals can manipulate. Examples of ape enrichment include the scattering and hiding of food, puzzle toys, differing scents and sounds, pinatas, clothing, boomer balls, ice, random feeding, bedding material, and positive reinforcement training.

Photo by: M. Brickner

Friday, May 23, 2008

The Writing on the Wall

In September 1991, the Zairian military went on a Kinshasa-wide rampage. The unrest quickly spread to the civilian population. To keep the hordes out of the compound where I and the bonobos lived, I slaughtered a sheep, and with its blood, wrote "AIDS" on the institute's walls. It worked. This photo was taken a few days later, with some of my workers. From Grains of Golden Sand:

In September 1991, the Zairian military went on a Kinshasa-wide rampage. The unrest quickly spread to the civilian population. To keep the hordes out of the compound where I and the bonobos lived, I slaughtered a sheep, and with its blood, wrote "AIDS" on the institute's walls. It worked. This photo was taken a few days later, with some of my workers. From Grains of Golden Sand:"From the tub, I sucked the sheep-blood slurry into the syringe. In three foot tall letters, I spray-painted the word “SIDA”—“AIDS” in French—on the cement block entrance wall. The blood ran dramatically in long, red fingers down the pale ramparts. It was a word that evoked cold dread. In those early years of the sickness, many believed that AIDS was an anti-African plot hatched by outsiders. Skeptics joked that the letters “SIDA” stood for Syndrome Imaginiare pour Décourager les Amoureux, the Imaginary Syndrome to Discourage Lovers. But people were learning that this so-called imaginary disease was a killer."

Photo by: D. Messinger

Photo by: D. Messinger

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Grains of Golden Sand Excerpt -- Mushrooms

I did not arrive in Africa until I was 30, but my journey started long before then. As a youngster, I longed for the tough and the untamed. I didn’t care for dolls. I was, instead, a strange little girl who played strange games, amusements that came from places in my mind that I could not fathom. Although generally well-behaved, I had bizarre compulsions to experience the outdoors and did so clandestinely when I suspected that it was a no-no, and openly otherwise.

When I was four, we lived on a farm across from a cranberry bog near South Carver, Massachusetts. One day my mother, who had already noted my distaste of indoor confinement, found me in the woods, stuffing mushrooms into my mouth. I refused to spit them out. Instead—I’d show her—I swallowed. Mom rushed me into the house, called the hospital, and followed their instructions. To induce vomiting, she made me drink heavily salted water followed by a mustard solution. Her report: the kid drank it all, glared furiously at her, and still refused to give up the mushrooms. When grilled, I admitted that I’d been consuming them for days. Finally, she relented, thinking, “All right, you little sneak”—perhaps that wasn’t the exact phrase—“you haven’t died yet.” I’m sure it stands out in her memory, but I don’t remember the details of that particular episode. In truth, I had sampled odd foods from the time I could walk. (I also stole snacks from the fifty-pound bag of dog food stored on the porch.)

When I was six, we moved to Waco, Texas. We were an Air Force family and mobility came with father’s uniform. Where before there were the lush woods in which I wandered at will, picking and pruning and gleaning the blueberry bushes like a wild creature, now it was rows and rows of boring, sun-baked suburbia. Here and there were precious strips of fallow, but the only wildlife they held were giant red ants and the horned toads that ate them.

Lacking untamed spaces—and perhaps rationalizing that it was my birthright—I began my career of childhood mischief. I persistently raided the neighbors’ fruit trees and wild plants, pretending that I was a deer browsing through, fattening myself for the coming winter. I was never apprehended, possibly because much of the fruit was left to rot anyway and possibly because I always took along my mongrel dog Pepi, who was really a “wolf” and loyal protector. From day to day, escapade to escapade, I was a feral creature, a Cro-Magnon, a trailblazer, an Australian aborigine, thriving by wits alone. There were no other people in my world, no buildings, no cars, no electricity. There was just nature and me.

I became the ringleader of a group of adventuresome friends. We raided squirrels’ nests, explored mossy drainage culverts under the streets, fished in rain puddles with bent safety pins, and cut open dead animals to see what was inside. In winter, during a rare Waco snowstorm, I built an “igloo” and pretended to be an Eskimo. I imagined killing seals, being pulled by huskies, and wondered what blubber would taste like. I pondered the rigors of glacial temperatures and whether I could survive wearing ten shirts, ten pairs of pants, and ten pairs of woolly socks.

Then, pursuing my father’s graduate school dreams, the family moved again. This time it was to 25 acres of undeveloped scrub south of Austin. There we lived for months in a shell of a condemned house that my dad purchased cheap at auction. It had been sawed into three pieces, moved to our property, and nailed back roughly together. While the well was being dug, we had no water and the north wind whistled through a building with no heat. This rurality was my delight and I could hardly be forced inside. I made a pact with the family that all my chores would be outdoors, which would excuse me from housebound duties.

Despite a dearth of edible plants, I continued to eat and taste wild foods and became, at least in my own mind, a wildcrafter. I chewed on mesquite beans, tried cooking cactus pads, chased armadillos, and hollowed out a den at the base of a sprawling cedar. I dined on mistletoe berries for years and then read somewhere that they were poisonous. I reasoned that the books were wrong because birds ate the sticky, translucent things. Surely they were edible, just as they were meant to be glued by bird beaks to branches for spawning fresh parasitic plants—if they were good enough for birds, they were good enough for me.

A few months after we moved to the ramshackle place, I was given two horses that the owner had no use for and didn’t want to feed. (She felt sorry for me because I had joined the pony club but had no horse to ride.) One was a 28-year-old, broken-down Thoroughbred, the other a blue-eyed white pony mare. The gelding’s name was “Biggie,” an ill-tempered, shaggy, sway-backed beast whose bony withers towered above my head. The pony was a half-wild creature that had never been trained properly. Because my father had left the military to return to school, we were poor, and with six kids, always on a tight budget. The family had little money to care for horses properly or to buy grain, a saddle, or even a decent fence. None of this mattered. I was determined to make it work.

My parents bought enough wire to construct a triangular pen anchored by three cedars where the animals could be kept, with ten bales of hay as my Christmas present. On weekends, I rode a half-mile to the main road whose shoulders presented a lush crop of weedy Johnson grass. There, cutting my fingers until they bled on the serrated blades, I pulled grass by hand, tied it into bundles and hauled it home. No sacrifice was too great. Every morning I arose at 5:30 to care for my beasts before school. Those were the best years of my childhood.

Horses set me free. I fashioned rope bridles and rode bareback. I became an explorer and rediscovered America. As a rancher, I scoured the range searching for lost steers. I was a hungry Indian scouting for bison. I stood on my steeds’ backs to steal the out-of-reach peaches and plums within a ten-mile radius. I imagined what it would be like to take a cayuse and follow the railroad right-of-way across America. I’d read about the Pan-American Highway and wondered if I could actually take a road all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

When I was four, we lived on a farm across from a cranberry bog near South Carver, Massachusetts. One day my mother, who had already noted my distaste of indoor confinement, found me in the woods, stuffing mushrooms into my mouth. I refused to spit them out. Instead—I’d show her—I swallowed. Mom rushed me into the house, called the hospital, and followed their instructions. To induce vomiting, she made me drink heavily salted water followed by a mustard solution. Her report: the kid drank it all, glared furiously at her, and still refused to give up the mushrooms. When grilled, I admitted that I’d been consuming them for days. Finally, she relented, thinking, “All right, you little sneak”—perhaps that wasn’t the exact phrase—“you haven’t died yet.” I’m sure it stands out in her memory, but I don’t remember the details of that particular episode. In truth, I had sampled odd foods from the time I could walk. (I also stole snacks from the fifty-pound bag of dog food stored on the porch.)

When I was six, we moved to Waco, Texas. We were an Air Force family and mobility came with father’s uniform. Where before there were the lush woods in which I wandered at will, picking and pruning and gleaning the blueberry bushes like a wild creature, now it was rows and rows of boring, sun-baked suburbia. Here and there were precious strips of fallow, but the only wildlife they held were giant red ants and the horned toads that ate them.

Lacking untamed spaces—and perhaps rationalizing that it was my birthright—I began my career of childhood mischief. I persistently raided the neighbors’ fruit trees and wild plants, pretending that I was a deer browsing through, fattening myself for the coming winter. I was never apprehended, possibly because much of the fruit was left to rot anyway and possibly because I always took along my mongrel dog Pepi, who was really a “wolf” and loyal protector. From day to day, escapade to escapade, I was a feral creature, a Cro-Magnon, a trailblazer, an Australian aborigine, thriving by wits alone. There were no other people in my world, no buildings, no cars, no electricity. There was just nature and me.

I became the ringleader of a group of adventuresome friends. We raided squirrels’ nests, explored mossy drainage culverts under the streets, fished in rain puddles with bent safety pins, and cut open dead animals to see what was inside. In winter, during a rare Waco snowstorm, I built an “igloo” and pretended to be an Eskimo. I imagined killing seals, being pulled by huskies, and wondered what blubber would taste like. I pondered the rigors of glacial temperatures and whether I could survive wearing ten shirts, ten pairs of pants, and ten pairs of woolly socks.

Then, pursuing my father’s graduate school dreams, the family moved again. This time it was to 25 acres of undeveloped scrub south of Austin. There we lived for months in a shell of a condemned house that my dad purchased cheap at auction. It had been sawed into three pieces, moved to our property, and nailed back roughly together. While the well was being dug, we had no water and the north wind whistled through a building with no heat. This rurality was my delight and I could hardly be forced inside. I made a pact with the family that all my chores would be outdoors, which would excuse me from housebound duties.

Despite a dearth of edible plants, I continued to eat and taste wild foods and became, at least in my own mind, a wildcrafter. I chewed on mesquite beans, tried cooking cactus pads, chased armadillos, and hollowed out a den at the base of a sprawling cedar. I dined on mistletoe berries for years and then read somewhere that they were poisonous. I reasoned that the books were wrong because birds ate the sticky, translucent things. Surely they were edible, just as they were meant to be glued by bird beaks to branches for spawning fresh parasitic plants—if they were good enough for birds, they were good enough for me.

A few months after we moved to the ramshackle place, I was given two horses that the owner had no use for and didn’t want to feed. (She felt sorry for me because I had joined the pony club but had no horse to ride.) One was a 28-year-old, broken-down Thoroughbred, the other a blue-eyed white pony mare. The gelding’s name was “Biggie,” an ill-tempered, shaggy, sway-backed beast whose bony withers towered above my head. The pony was a half-wild creature that had never been trained properly. Because my father had left the military to return to school, we were poor, and with six kids, always on a tight budget. The family had little money to care for horses properly or to buy grain, a saddle, or even a decent fence. None of this mattered. I was determined to make it work.

My parents bought enough wire to construct a triangular pen anchored by three cedars where the animals could be kept, with ten bales of hay as my Christmas present. On weekends, I rode a half-mile to the main road whose shoulders presented a lush crop of weedy Johnson grass. There, cutting my fingers until they bled on the serrated blades, I pulled grass by hand, tied it into bundles and hauled it home. No sacrifice was too great. Every morning I arose at 5:30 to care for my beasts before school. Those were the best years of my childhood.

Horses set me free. I fashioned rope bridles and rode bareback. I became an explorer and rediscovered America. As a rancher, I scoured the range searching for lost steers. I was a hungry Indian scouting for bison. I stood on my steeds’ backs to steal the out-of-reach peaches and plums within a ten-mile radius. I imagined what it would be like to take a cayuse and follow the railroad right-of-way across America. I’d read about the Pan-American Highway and wondered if I could actually take a road all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Hello!

Welcome to my blog:

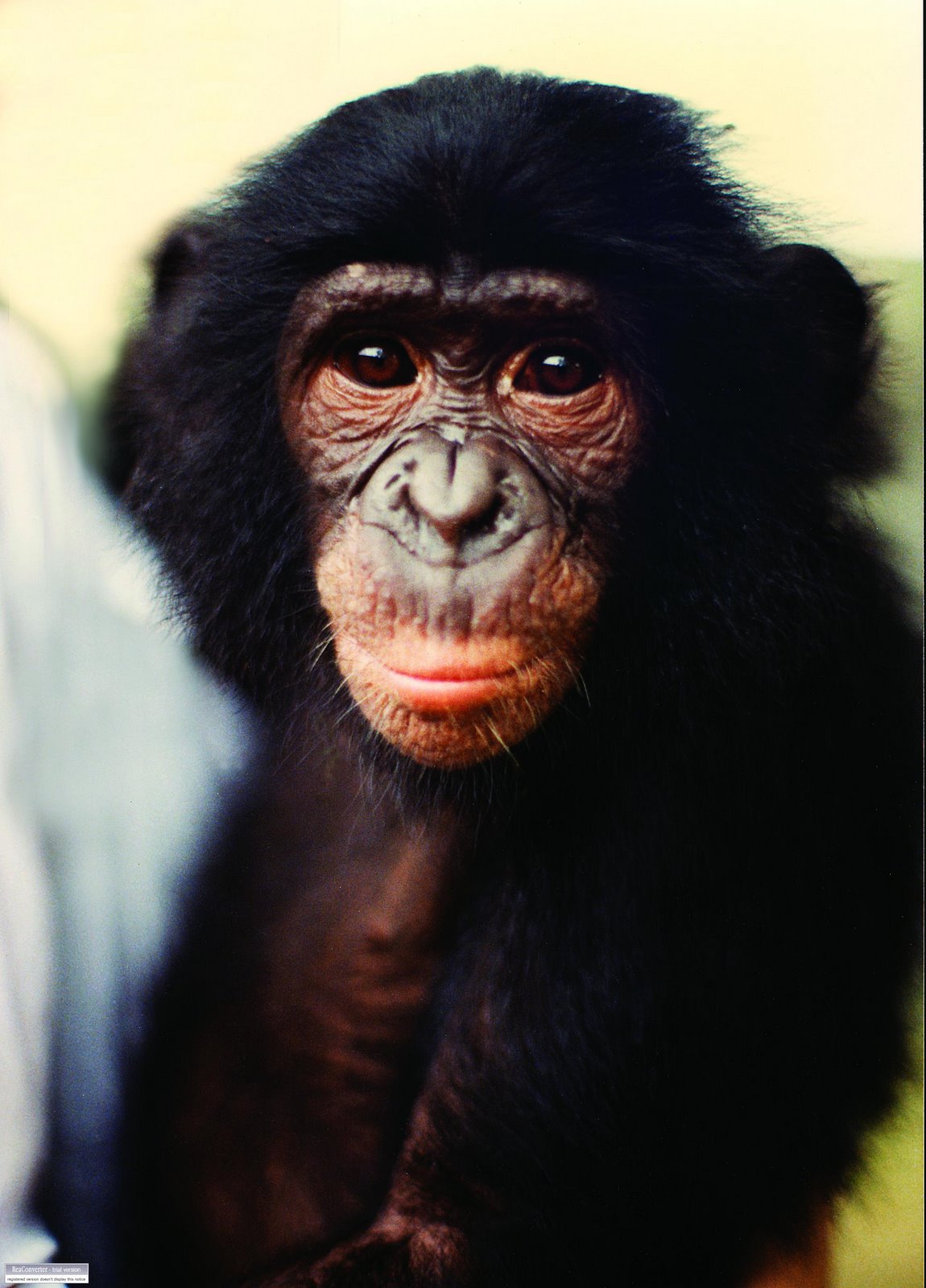

Bonobo, bonobo, bonobo! -- what a strange name for an ape creature. At first glance, it looks like a chimp, but at second regard, it doesn't ACT like a chimp at all. Almost humanlike in behavior, zookeepers and scientists have learned that bonobos, unlike chimpanzees, have the habit of using sex to disfuse social tensions. Bonobos are the ONLY species of animal -- besides us, that is, to have sexual relations outside of procreation. And unlike other species of apes, the bonobo has never been known to commit infanticide.

My blog is devoted to the bonobo, with spin-off subjects of conservation interest. In the months to come I will talk about the illegal exotic animal pet trade, the bushmeat situation, and the destruction of the forest to logging as well as gold, coltan, and diamond mining in central Africa. A percentage of proceeds from my book, Grains of Golden Sand will go to support the Lukuru field conservation project.

Having lived in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC) for 14 years as a volunteer and "freelancer", I did many things such as studying zoonotic viruses for the World Health Organization, founding a children's magazine, working as a "vet", and aiding various conservation organizations. In the future, Iwill share with readers topics such as the effects of AIDS, the story of the basenji dog, the treatment of women and children, Congolese politics, how parrots are trapped, and African songs and stories.

Finally, because since 1974, I am, and have always been a "zookeeper" at heart, I want to share what zoos are doing worldwide to help today's generation understand and act to preserve animals in the wild, and in so doing, maintain a sustainable future for the planet. There will be many stories about zoo animal "ambassadors" with the links to projects in the field.

Welcome to my blog:

Bonobo, bonobo, bonobo! -- what a strange name for an ape creature. At first glance, it looks like a chimp, but at second regard, it doesn't ACT like a chimp at all. Almost humanlike in behavior, zookeepers and scientists have learned that bonobos, unlike chimpanzees, have the habit of using sex to disfuse social tensions. Bonobos are the ONLY species of animal -- besides us, that is, to have sexual relations outside of procreation. And unlike other species of apes, the bonobo has never been known to commit infanticide.

My blog is devoted to the bonobo, with spin-off subjects of conservation interest. In the months to come I will talk about the illegal exotic animal pet trade, the bushmeat situation, and the destruction of the forest to logging as well as gold, coltan, and diamond mining in central Africa. A percentage of proceeds from my book, Grains of Golden Sand will go to support the Lukuru field conservation project.

Having lived in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC) for 14 years as a volunteer and "freelancer", I did many things such as studying zoonotic viruses for the World Health Organization, founding a children's magazine, working as a "vet", and aiding various conservation organizations. In the future, Iwill share with readers topics such as the effects of AIDS, the story of the basenji dog, the treatment of women and children, Congolese politics, how parrots are trapped, and African songs and stories.

Finally, because since 1974, I am, and have always been a "zookeeper" at heart, I want to share what zoos are doing worldwide to help today's generation understand and act to preserve animals in the wild, and in so doing, maintain a sustainable future for the planet. There will be many stories about zoo animal "ambassadors" with the links to projects in the field.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)