The photograph shows me with a client and her dog, in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). I was treating the German Shepard for dermatitis, a common problem due to a lack of commercial diets. Owners often tried rice, palm oil, and canned sardines which was an incomplete diet.

From

Grains of Golden Sand: "It seemed that everyone moonlighted in Kinshasa. The more ambitious had a combination of three or four full and part-time occupations. Most of the institute’s staff worked in other labs or hospitals or were studying different professions in schools. A few of our own department heads, such as a parasitologist and virologist, were professors who part-timed at the INRB. After an unsuccessful attempt at raising chickens, Karhemere began teaching part-time. The institute’s administrators looked the other way when he came in at noon or was entirely absent.

"Without exception, government employees weren’t given a living wage. A physician working in a state hospital might earn three or four dollars a day, plus an abysmal benefits package. Worse, civil servants were paid only at random intervals. Months would go by before there was enough pressure and threats of strikes to force the government to release a chunk of the budget for its workers.

"In the Zairian way, I too found something else to do. My first job was the animal department and my second was the artwork, so “veterinarian” was my third. Unlike the others, I didn’t seek the calling; it was thrust upon me.

"Curiously enough, my first “consultation” was with a human. It was probably in 1992 when she swept in—an influential grande dame in the Belgian community, tall, refined, and wearing a chic short dress. She must have considered me a fright in my usual rubber-tire-bottomed flip-flops and faded African print smock.

"But that day her mind was not on haute coutiere. She came to ask me to help her daughter, who had foot dermatitis. “You must be mistaken,” I said. “I’m not a doctor. I work with animals.” But she insisted that I listen to her problem. The reason Madame came to me, she said, was that she remembered Dr. Salaün remarking how the bonobos I cared for suffered from human afflictions. She’d tried several physicians without success, and now the latest one wanted to test for fungus. She needed advice on how to have the test run at the INRB. Otherwise, she was determined to take the girl back to Europe for treatment. Voice breaking, she explained that she was at her wit’s end because her daughter had been suffering for months. The pre-teen girl had cracks so deep in the bottoms of her feet that they bled and every step was painful.

"I agreed to help and explained that fungus was both difficult and slow to grow in culture. Luckily, the tests were still available at the institute, and she could bring her daughter in to have a technician take a sample. I asked her what anti-fungal treatment was being used because it would need to be discontinued so as not to interfere with the test.

"She explained that the latest approach in a long string of trials was strict asepsis. The girl’s feet were kept covered day and night with clean white socks, removed only twice a day when the feet were soaked in bleach water. “Hmm,” I said. “That seems a strange recommendation for fungus.” I withheld further skepticism of the remedy but said that for the test her girl would have to skip the bathing. “And remove those socks and open those feet up to fresh air,” I advised. “Don’t let her wear shoes. Open sandals should be fine; look, like these,” and showed her my woe-begotten pair.

"The lady and her daughter didn’t show on the prearranged testing date, and I wondered if she had indeed taken the girl to Europe. Months later, she breezed into my office and plopped down a box of Belgian chocolates on my desk. “What kind of miracle was that?” she asked. “As soon as we took off the socks, it started getting better. Within two weeks, her feet were completely healed! Bravo!”

“No miracle; just good sense ,” I replied. “Due to the high humidity, a lot of people suffer from skin problems in the tropics. Without testing, we’ll never know now if it was fungus, but many skin afflictions respond to a simple uncovering and drying. We lucked out that the easiest thing worked.”

"That success rippled throughout the expat community. Scuttlebutt had it that there was a woman with a certain proficiency in common-sense doctoring. Many seemed to think that if there was an animal nurse who could cure a human, imagine the wonders she could work with Spot and Kitty. By 1993, we were practically the only vet game in town. From a handful of magic beans, I’d cultivated a rich crop of skills, and, it seemed, almost endless opportunities to learn more."

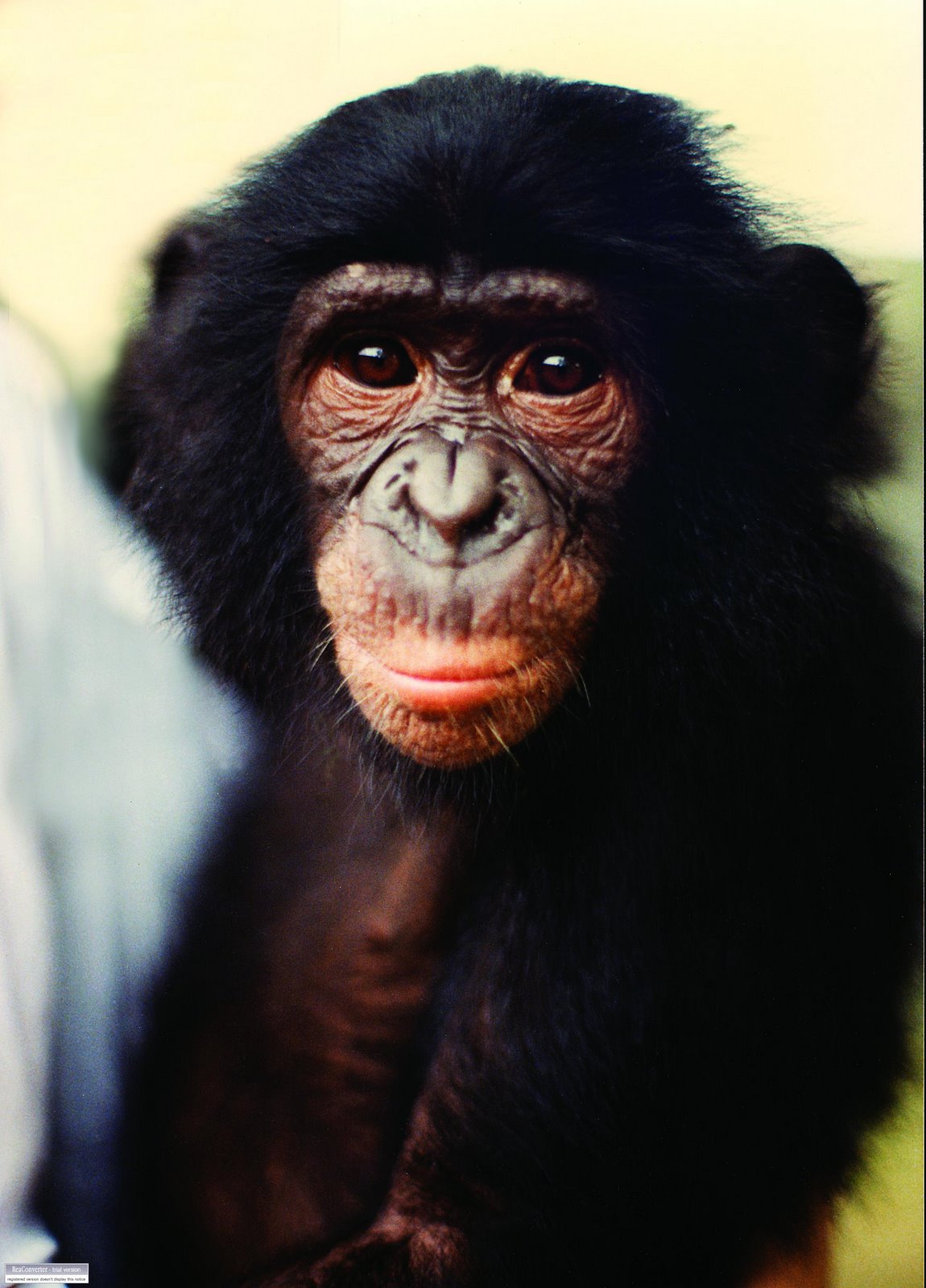

Akili, a 28 year old male bonobo from the San Diego Wild Animal Park, recently arrived at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens to serve as the primary breeding male for Lorel, Kuni, and Lori. He weighs just over 100 pounds and is the father of three offspring. Akili has not sired any babies since Jumanji, due to to social group changes at his former home.

Akili, a 28 year old male bonobo from the San Diego Wild Animal Park, recently arrived at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens to serve as the primary breeding male for Lorel, Kuni, and Lori. He weighs just over 100 pounds and is the father of three offspring. Akili has not sired any babies since Jumanji, due to to social group changes at his former home.

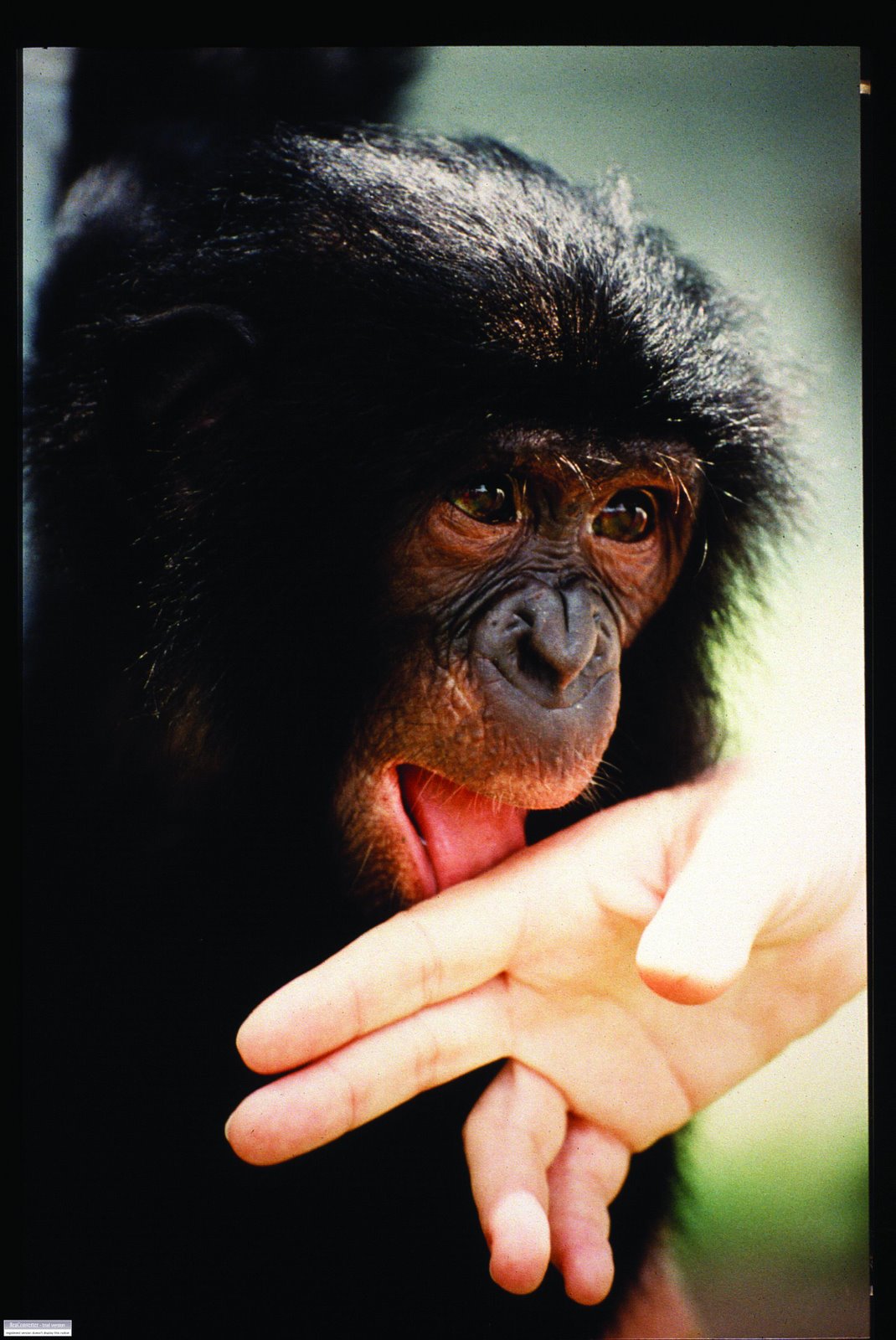

Behind the animalerie where the orphaned bonobos lived was a bamboo grove, grassy yard, and a few trees. When the bonobos were young, they would get playtime outside, where they could run about and climb the trees. Always, they were accompanied by a caretaker.

Behind the animalerie where the orphaned bonobos lived was a bamboo grove, grassy yard, and a few trees. When the bonobos were young, they would get playtime outside, where they could run about and climb the trees. Always, they were accompanied by a caretaker.