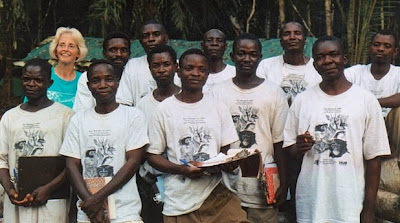

"For now we continue to support the work of ICCN in the Anga Secteur of Parc National de la Salonga, strengthen our relationship with the Iyaelima people living exclusively inside the national park, continue lobbying and monitoring across the whole of the Lukuru zone of influence and maintain our focused energies around the Bososandja forest block. In addition, we meet annually with the greater population of the region; a formal reunion with the local population, representatives of all clans, traditional chiefs, and authorities.

"This typically involves a three-day commitment of exchange. We update the communities on the activities of the Lukuru Project, discuss their ideas about our role, and exchange assurances. The population reports on their conservation activities and challenges. So for example, last year we discussed the problem of poachers around Yasa for commercial bushmeat trade.

"The annual meetings involve a lot of back-and-forth, emotion and shared humor. Over the course of the days of meeting, the population sequesters themselves periodically to talk amongst themselves and then come back to me formally with thoughts. Often their requests are either out of the purview of the Lukuru Project or unrealistic. But, we always strive to have a common outcome.

"Some of the current obligations made on behalf of the Lukuru Project are:

1) I have agreed to bring an engineer to Yasa to evaluate the suitability for sinking a tube well.

2) I have agreed to research the process of making soap. There will be further discussion about this based on what I learn.

3) The population has requested that the Lukuru Project have a professional garde formation. I have agreed to recruit addition personnel for the Bososandja. This will entail formal training and equipping.

4) The population wants assistance to build houses to help host guests in the future.

5) I have agreed to provide tin roofing for the school and help develop the curriculum. They requested that I build a house for the Lukuru Project in the village."

Photos by R. Ross