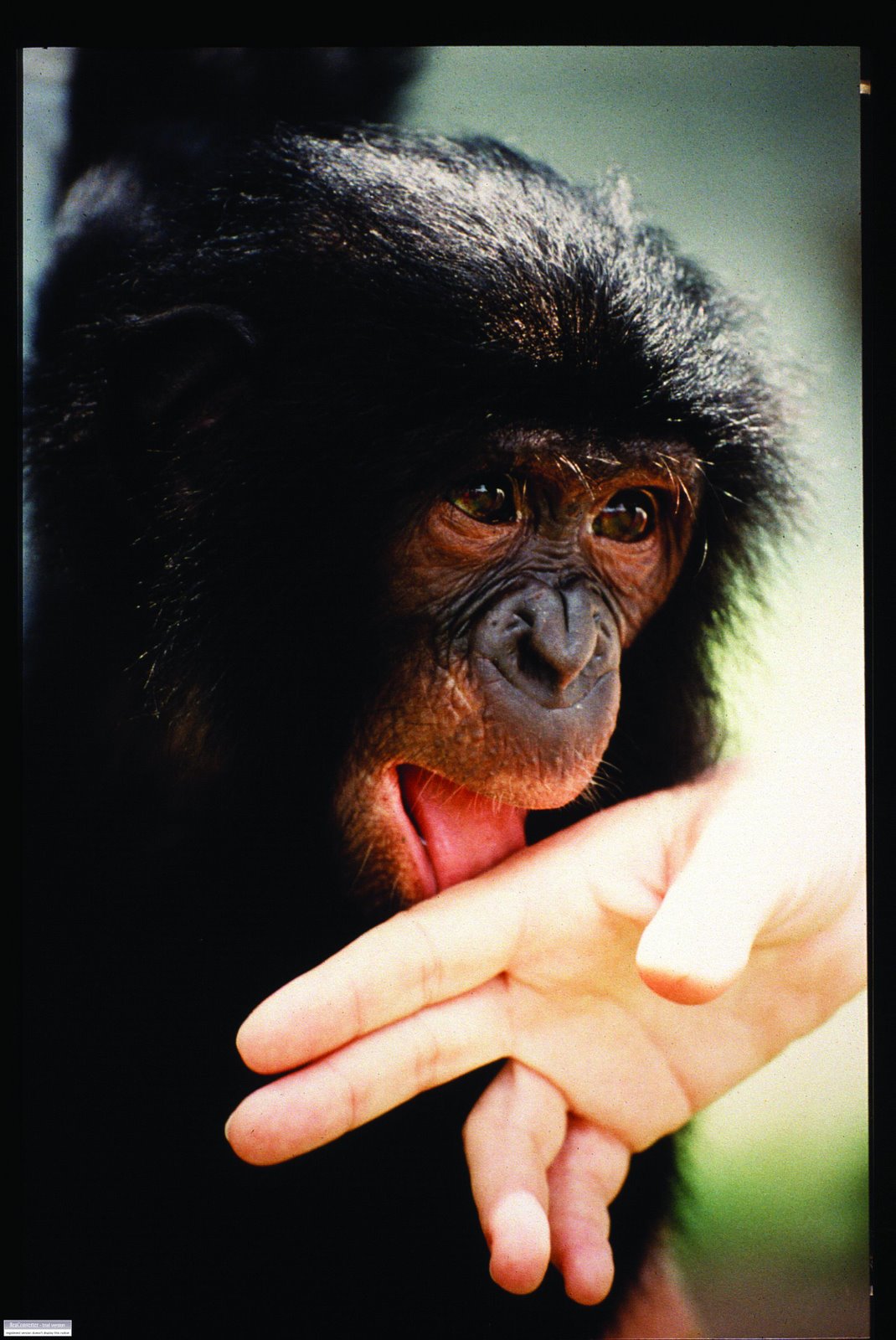

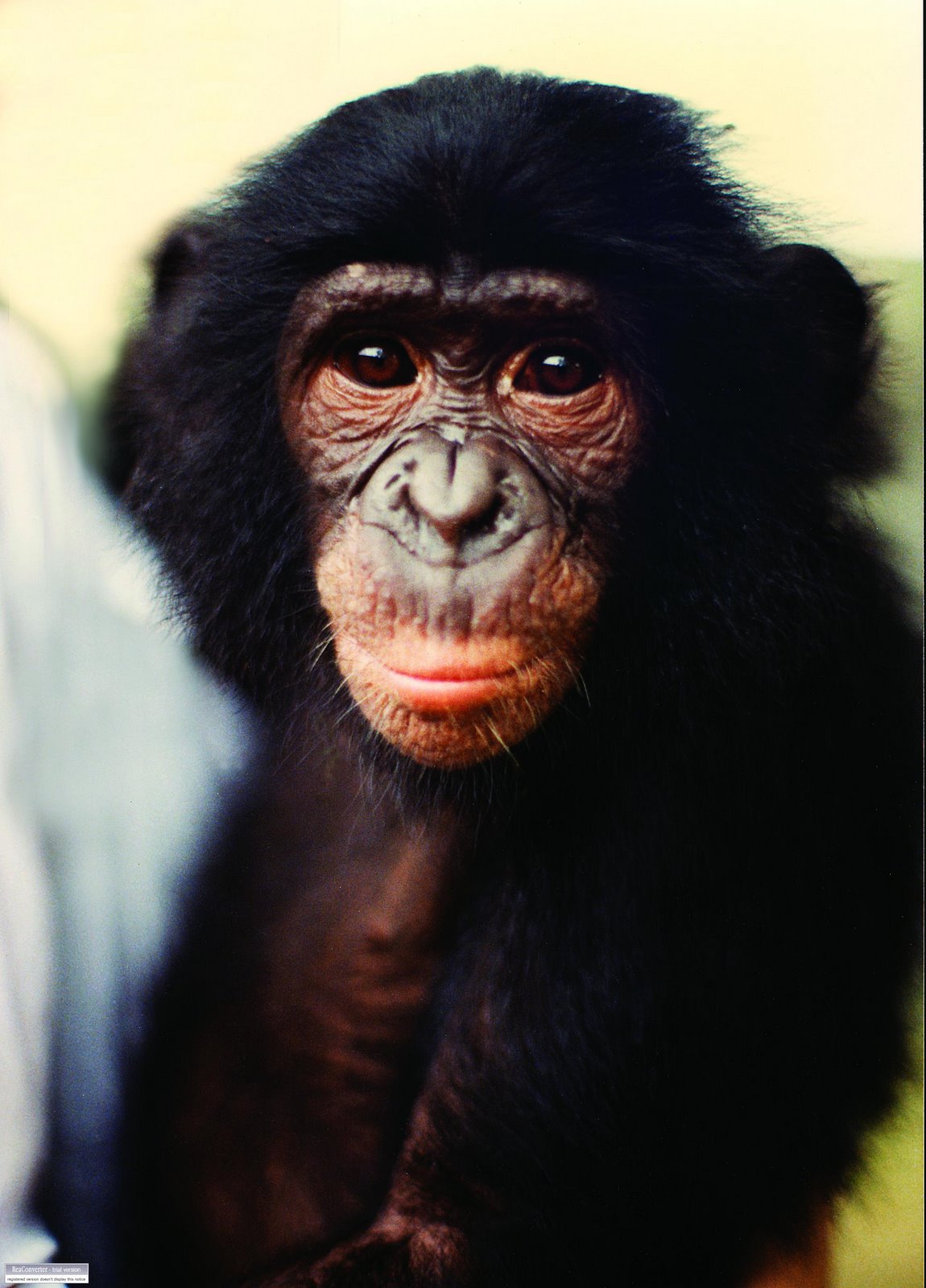

Kizito and I created an eight page educational booklet for the Milwaukee County Zoological Society. In it we told a local legend from a village where bonobos were not hunted:

Kizito and I created an eight page educational booklet for the Milwaukee County Zoological Society. In it we told a local legend from a village where bonobos were not hunted:"Once, in a village not far from Lake Mai-Ndombe, there lived a courageous young woman named Miesi. One day Miesi decided to go by herself to the fields, as her sisters were busy. But the forest was dangerous because of a great tribal war. On the path deep in the forest, she was surprised by a group of warriors from the enemy tribe. They demanded nastily, “Whoa, where are you going, woman?”

“I am going to my field of bananas,” she responded bravely.

In spite of her fear, she kept her wits and reproached them: “Watch out. My husband, the celebrated great warrior, is behind me with his band of hunters. Run away quickly before they find you here.”

The warriors broke out in laughter; they did not believe her story. “We are not blind, woman! We can see that you are by yourself! Ha ha! Prepare to die!” With that, they pointed their spears at her. Trembling, the poor Miesi thought that her last hour had come.

Just as they were about to dispatch her, a great war cry burst like thunder from the forest. Behind the young woman, the trees tossed violently. The men were petrified. Then a band of bonobos surged forward, throwing branches toward the enemy and screaming their cry of attack. The warriors, who knew the strength and intelligence of the species, pleaded to Miesi, “Pardon us, woman! Have pity!” But the bonobos continued to advance. The warriors abandoned their weapons and fled.

Miesi went back to her village and told her astonishing story, which was transmitted from father to son until our days. Maman Miesi was the ancestor of today’s tribe. To repay the debt for Miesi’s life, the people don’t eat bonobos."

For a while, she menaced as a Hurricane category one, but then Fay wiggled and waggled and stalled in the middle of the state before blowing in as a tropical storm that dumped up to 20 inches of rain in some areas over several days, starting Wednesday, the 20th of August.

For a while, she menaced as a Hurricane category one, but then Fay wiggled and waggled and stalled in the middle of the state before blowing in as a tropical storm that dumped up to 20 inches of rain in some areas over several days, starting Wednesday, the 20th of August.