In the capital city of Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), exotic animal infants were exploited as pets. Primates -- both apes and monkeys, were seen as desirable because they were engaging and human-like. From Grains of Golden Sand:

In the capital city of Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), exotic animal infants were exploited as pets. Primates -- both apes and monkeys, were seen as desirable because they were engaging and human-like. From Grains of Golden Sand:"Few challenged the legitimacy of selling primates. Theoretically, apes were a “protected” species, but by law, a person only needed the proper document to “own” one. The first attempt to control the trade was made in September 1990 when Jane Goodall convinced authorities to confiscate apes from sellers. American diplomats noticed animals openly displayed in front of their offices and took the time, effort, and energy to track down the proper authorities for seizure. Sometimes, the lengthy execution of the cumbersome paperwork and the requisition of military backup resulted in the creature being sold in the meantime. Or perhaps a tip would filter back to the seller, and the animal would have “vanished” by the moment of the raid. During the year that animals were being seized, a half-dozen chimpanzees were collected. Thus warned, the comerçants no longer openly displayed their ape wares.

"Confiscation works but only partially. It was not a panacea, but only one step in controlling trade by eliminating “pity-purchases” from impulsive customers. Government seizure drives the market underground where it becomes invisible and nearly impossible to monitor. The sellers, not surprisingly, became exceedingly secretive and cagey about their enterprise.

"The seizures had little direct effect on the comerçants themselves: they did not own the apes they sold. An owner would leave an animal on consignment at the market and specify a price to which the peddler would add his own margin of profit. If the chimpanzee or bonobo was sold, the owner would be given his price and the seller would pocket the difference. All risk fell on the owner of the animal, not the retailers. If an animal died from illness or escaped, it was understood that it was the owner’s tough luck. A surprise seizure was in the “act of God” category.

"It was no great hardship upon the comerçants if they were no longer allowed to display apes in public. In the African world of the big hassle, hiding the goods was simply another nuisance—the price of doing business. The primates were kept hidden, either at the owner’s house or close to the market where prospective customers were conducted to the merchandise. Similarly, seizure was never a financial disaster for the animals’ owners. Selling apes was largely a one-time deal for them. These travelers brought chimpanzees or bonobos from the bush to Kinshasa by convenience, coincidence, or calamity. The economic lesson of seizure was thus lost on someone who likely would never again transact another chimpanzee or bonobo sale."

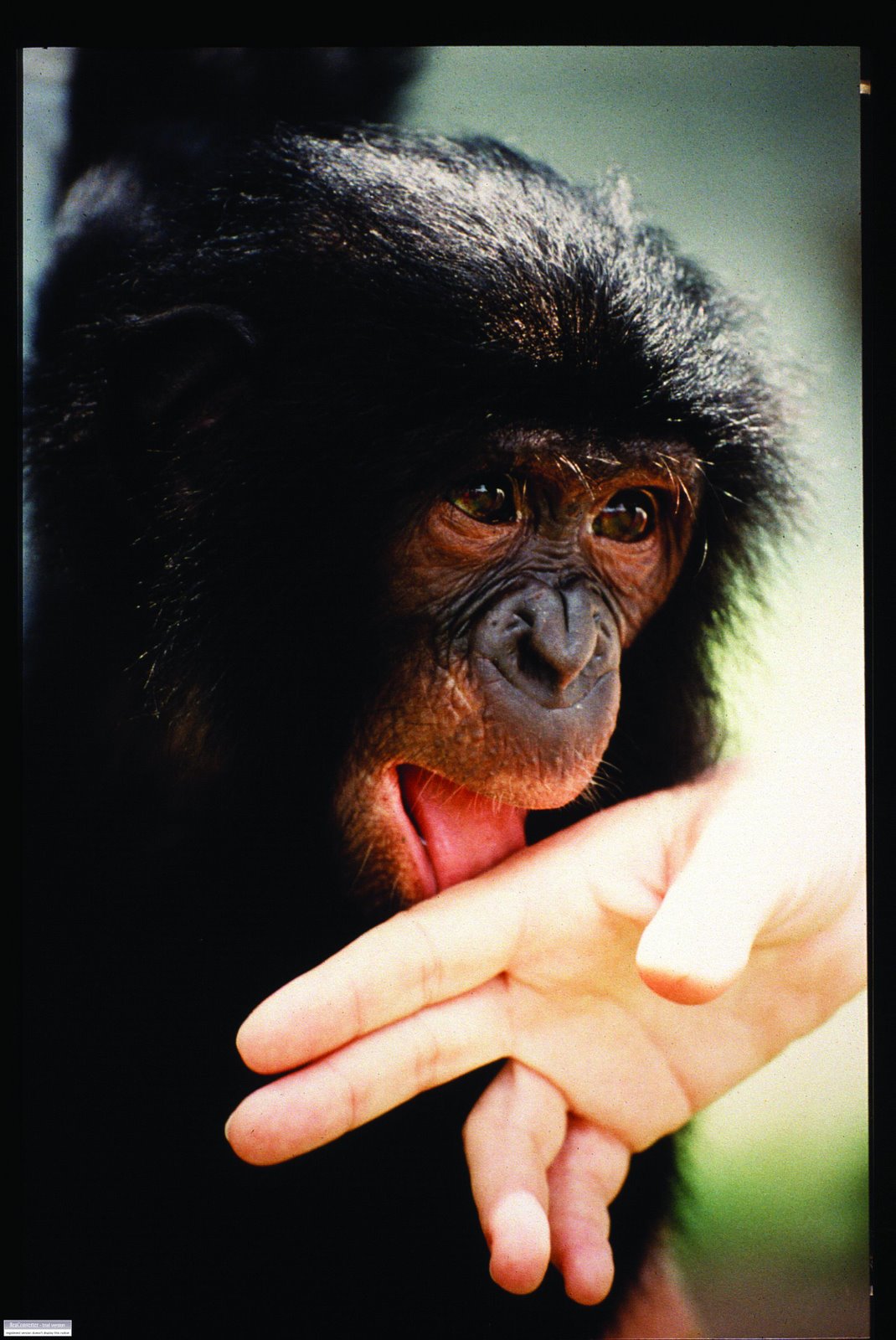

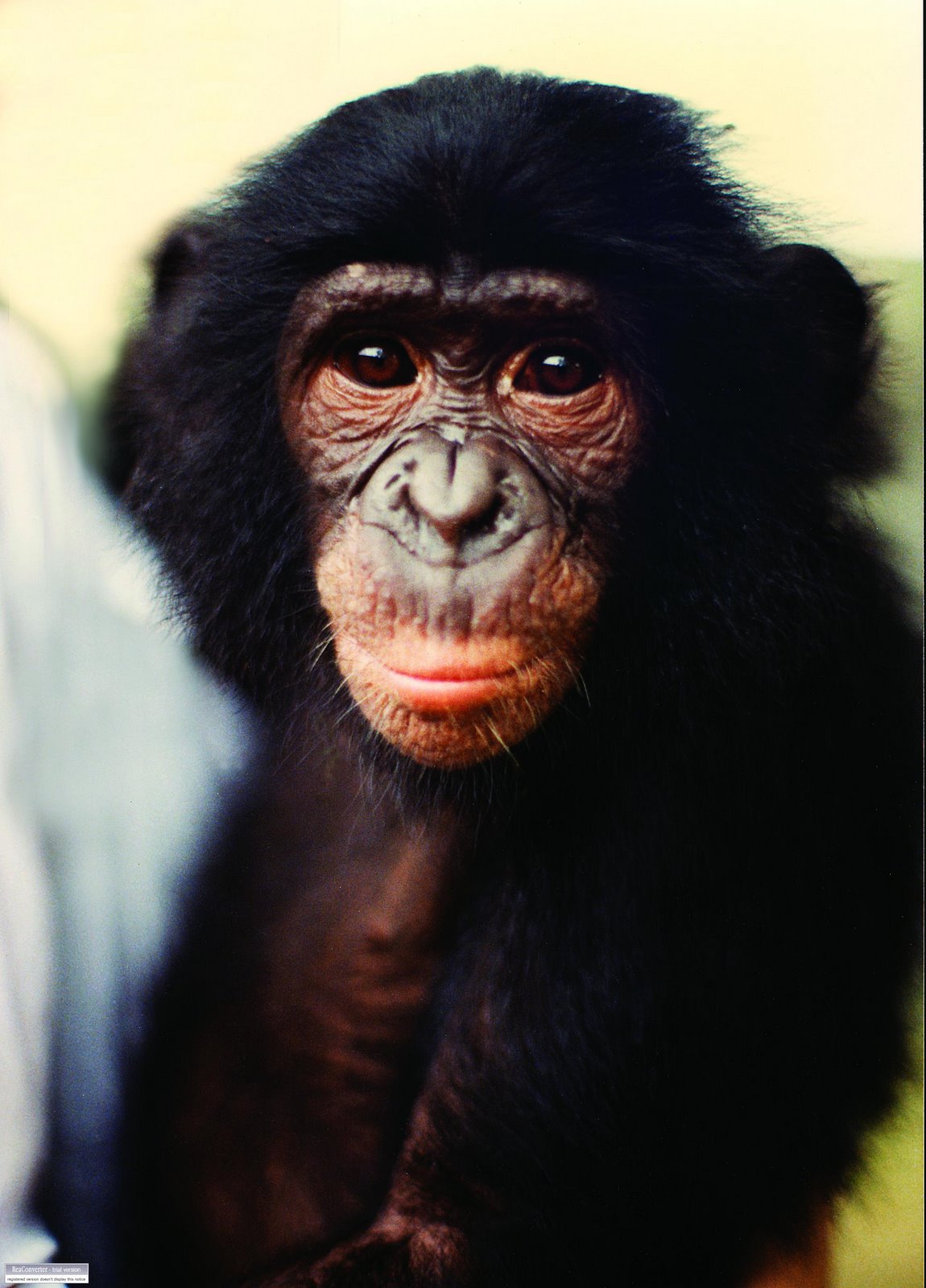

The photograph shows two very young, and very ill chimpanzees in the main market, near the downtown train station, close to embassy row. Besides their small size, they can be determined to be critically ill by the swollen tissue around the eyes. Their "handlers" were not the owners; the animals had been placed on consignment at the market, with the understanding that if it died, the loss would be for the owner.

I discovered through several years of interviewing transporters, owners, villagers, and market sellers, that the "pipeline" of apes was incidental, (in contrast to that of African grey parrots) and ape babies were not comodities that people sought. A live, baby ape was a rare occurrence in the village, and travelers would be persuaded to gamble on a purchase of a few dollars.

No comments:

Post a Comment